Just outside a Palestinian restaurant, named “al-Bayt” in the recently recognized village of Ayn Hawd southeast of Haifa, a table and two chairs stand precariously balanced on a steep slope. From a distance it is a pretty scene that promises the serenity of a picnic. On closer look, there is deformity and fragility. Together they offer an incisive reflection on those many moments when the Palestinian everyday in Israel meets the persistent apprehension and restlessness of memory. Sharif Waked’s installation Khumus tells of the inextricability of two communions—one that is untenable in the present and another in the past that has been made absent.

On this slippery slope that makes vivid the very condition of asymmetry, the work of the hand-made interrupts the pre-manufactured. Delicate extensions flirt with the idea of organic growth. The chair has unnaturally long legs; they lean forward looking for footing in the asphalt while flaunting a shaky giraffe like elegance. The side that is lower on the slope squarely faces its other. But this facing is not an instance of power; indeed the handmade additions are an artistic fortification, a reinstatement of fragility. The desire to respond to the invitation to sit is met by the precarity of that wish.

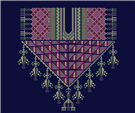

HUMUS_1(2).jpg)

The table’s surface is another site of both visceral desire and repulsion. Two bowls of chickpeas interrupt the pristine top, suggestively hanging underneath. The bowls are the supplement; an excess that defines and distinguishes. They imbue the table with a subtly executed but sharply experienced sense of a body. The chickpeas in the bowl could have once been a delicious and protein-packed dish of humus—itself a site of a seemingly endless contest over cultural ownership (Palestinian, Lebanese, Israeli). The temptation to partake is tangible. At the same time, the delicate threads sprouting from each pea induce a deeply corporeal sense of restraint. The sprouting chickpeas offer the hope of organic growth alongside the smell of inevitable decay. The meal and the setting are seeped in dysfunction. The deformity of the table and chairs and the sprouting chickpeas reveal the blurry lines between the ripe and the rotten, just as the uneaten meals and the empty chairs conjure the specter of enforced absence.

HUMUS_2.jpg)

In the Presence

Khumus touches on and tugs at the conditions of “coexistence” in Israel. Its title plays with the shibboleth of Hebraized Arabic when Mohamad becomes Mokhamad. The deformed but elegant dining set stands, in all its instability, in a raw conversation with al-Bayt. At this and many other restaurants the Palestinian minority and the Israeli majority forge a tenuous culinary concord, structured by uneven patterns of production and consumption.

It is none other than Muahmmad Abu al-Hayja, the founder and leader of the Association of Forty that is al-Bayt’s proprietor. Like many Palestinian contractors, some Ayn Hawdians made their living “building other people’s homes.” In this particular case, some Palestinians labored in what had been their homes, under the watchful eye of the settlers who had now appropriated them. The colony, established in 1953, had been the village of Ayn Hawd and stands now as a bohemian testament to Israeli appropriation and confiscation of Palestine. Today, six decades after their original displacement from their seven hundred year old village, a small number of these Palestinians announce their shaky class arrival with stone and marble houses. Adorned with fountains and Roman columns, these grandiose structures stand in stark juxtaposition to the modest single floor homes that most people live in. Amidst this web of refugees, displacement, and newly realized profit margins stands Abu al-Hayja’s turn to the culinary.

Al-Bayt quickly garnered acclaim as one of the Galilee’s best-kept secrets. For some aspiring middle class Israeli Jews, the restaurant is the end point of that prototypical weekend journey. With teens in the loudest of popular fashion and grumpy children in tow, they arrive hungry after their pursuit of the much-desired destination (that secret place that one hopes to discover and make their own; except as it turns out, everyone has read the same food review in the supplementary weekend edition of Haaretz). They search for “the good and natural life.” At al-Bayt’s long tables of food, they take in “a breathtaking view of wide horizons…[and] the feeling of…having the world at one’s feet.”[1]

The aspiring Israeli middle class that comes to al-Bayt differs from the more ensconced elite down the hill in the village-turned artist colony of Ein Hod. There, the “good life” is based on destroying the Palestinian other and re-inscribing it as a “found object.” (For more on this process, see the work of Susan Slyomovics and Rachel Leah Jones). At al-Bayt, the encounter with the national self and environment is based on interpolating the Palestinian as Israel’s Arabs. The shakiness of this co-living is most apparent in those moments when Israeli nationalism and the consumption of “the Arab” are mutually exclusive. One such moment was in October 2000 when Palestinians mobilized in solidarity with the second intifada in the West Bank and Gaza and Israelis boycotted Palestinian establishments en masse. Khumus thus pierces and lays bare the culinary limitations of “co-existence” and the exchanges of production and consumption that make communion in the present a ramshackle experience.

HUMUS_4(1).jpg)

Of absence

The unsound character of communion in the present is also constituted by absence. With the uneaten, almost rotting chickpeas and the empty chairs, Khumus tells the story of temporary fleeing and the intention of return. It calls forth an earlier but still lived moment: “Deir Yassin had a huge influence of the evacuation of Talibiya [in Jerusalem]. The Arabs were scared…they left their meals on their tables…. There really were meals still on the tables. The Arabs thought it was a matter of two or three days before they would return to their homes.”[2] Khumus is a testament to this temporary absence that has been made permanent. This disconcerting and funny sculpture highlights how that absence continues to constitute the now and claim the present.

It is this absence that explodes the pretense of a “normal” Palestinian daily life in Israel. This installation offers a trace of sorts. But this is a trace that continues to grow, dangerously close to decaying. Khumus forcefully evokes that which once was, but its frailty renders the installation itself ephemeral. Khumus is not and can never be a monument. The condition of the temporary and the artistic rejection to monumentalize are indications of the depth and extent to which Palestinians in Israel need not commemorate. The enforced absence of Palestine is always present.

Israeli parliamentarians missed this lesson when they enacted “The State Budget Law Amendment” popularly known as the “Nakba Law,” last month in the late evening of 22 March 2011. Communities and organizations are now subject to fines if they publically challenge the founding of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state or if they “commemorate Israel’s Independence Day or the day on which the state was established as a day of mourning.” The amendment focuses on the “rejection of the democratic state” of Israel and the “dishonoring of the national flag” of Israel. But for Palestinians the nakba is not about Israel, it is about Palestine. In criminalizing memory these parliamentarians have ironically brought Palestinian mourning into the legal language of the state. But the presence of absence is not restricted to any particular day; it constitutes what it is to be Palestinian and what is to be Israeli.

About a year ago on BBC’s Hardtalk, deputy prime minister Dan Merridor made an uncharacteristic slip in his usually flawless English: “We want the Palestinians to come into the table.” Khumus dismantles the recurring trope of this piece of furniture. It explodes the premise of an even playing field that has resulted in a relentless and ever evolving apartheid logic for Palestinians under occupation. But Khumus tells of another set of meetings at the table, that of the Palestinian with and in Israel, and with and in the presence of absence. As with much of Waked’s work, one does not know whether to laugh or cry.

[1] Jonas Frykman and Orvar Lofgren, translated by Alan Crozier, Culture Builders: A Historical Anthropology of Middle Class Life (New Rutgers University Press, 1987), 54.

[2] Nathan Krystall, “The Fall of the New City 1947-1950,” Jerusalem 1948: The Arab Neighbourhoods and Their Fate in the War ed. Salim Tamari (The Institute of Jerusalem Studies and Badil Resource Center, 2002), 101.

![[Sharif Waked, Khumus (2008). Image from artist`s archive]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/(K)HUMUS_5-1m.jpg)